Reforming an experiential pharmacology curriculum for clinical pharmacists

Teaching a new generation of clinical pharmacists

The landscape of pharmacy education is continuously evolving to adapt to the increasing professional scope and needs of healthcare. Over time, the pharmacist’s role has changed, and more clinical expertise and training is now needed to suit their growing role as essential health care providers. Globally, many educators have embraced the transition from traditional Bachelor of Pharmacy degrees to a Doctor of Pharmacy (PharmD) degrees, to meet the rising demand for clinical pharmacists.

Imam Abdulrahman bin Faisal University (IAU), one of the most prominent academic institutions in Saudi Arabia, has recently established a College of Clinical Pharmacy (COCP) – a pioneer school of pharmacy aiming to train new generations of young clinical pharmacists that not only have the capacity to carry out essential healthcare roles but also boast strong scientific backgrounds and aptitudes for research. The COCP was established in 2013 and its six-year undergraduate PharmD programme has recently been awarded national accreditation.

I joined the fledgling college in 2015, where I was appointed as an assistant professor in the pharmacology department responsible for the delivery of pharmacology courses to all affiliate IAU Health Colleges (including colleges of Medicine, Clinical Pharmacy, Nursing, Applied Medical Sciences and Public Health). I was assigned to teach basic and systems pharmacology to both undergraduate medical and pharmacy students. In all courses delivered annually, only one has an experiential laboratory component highlighting the use of animals in research– an introductory pharmacology course delivered to third year PharmD students. Along with the theoretical component, this experiential lab-based component is delivered to approximately 70-90 students (roughly 40% male and 60% female) every year.

My story

As a graduate of pharmacy myself, I recall being asked one very specific question during admission interviews in Saudi Arabia: ‘How do you feel about handling mice?’. It was at a very early stage in my academic career where I was first exposed to laboratory animals. I was trained to handle lab mice and frogs, to repeat experiments that had been conducted for at least a decade prior. While I was grateful for such exposure as it offered a chance to gain a rare skill set and the confidence to handle animals in the lab, I was aware that there was an element lacking in our education.

After completing my undergraduate degree in pharmacy, I was awarded a fellowship by the Saudi Ministry of Higher Education to undertake an MSc. and PhD in Drug Discovery and Pharmacology at King’s College London. I had the opportunity to learn from some of the brightest

in vivo scientists and researchers in academia and industry and developed a keen appreciation for the vital role of animals in research and the responsibilities of undertake this work as a scientist. Exposure to such structured training and licensing requirements made me aware of the principles I now seek to instill in my current academic institution.

Animal handling skills for clinical pharmacists? Should we stick to what we know?

In 2015, the lab curriculum being taught at the COCP was nearly identical to the one I myself had been taught during my own undergraduate degree nearly a decade prior. It was a curriculum that solely contained dated experimental exercises involving animal models. While the lab content focused on developing technical animal handling skills, it lacked an essential core element:

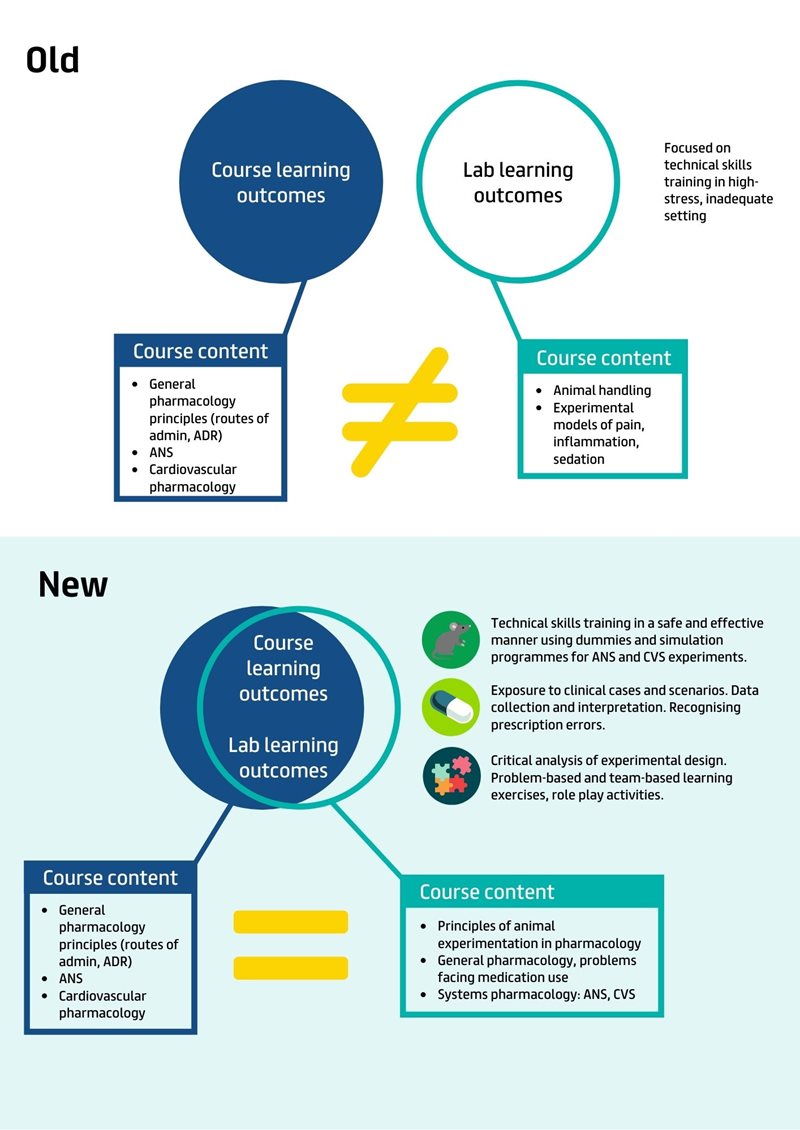

a conscious and structured approach focused on the responsible use of animals in research. Another obvious shortcoming of the dated lab curriculum was its poor alignment with the course and programme learning outcomes. This is a common problem facing most newly developed academic programmes transitioning from traditional science-intensive degrees to clinical pedagogies. In response to this, many PharmD and medical degree programmes have effectively dropped the experiential component of pharmacology teaching, favoring instead a problem-based approach focused mainly on the development of skills relevant to a clinical setting. The alternative practice commonly observed by many institutions, including our own, is to retain the same old experiential pharmacology material and deliver this unchanged despite its obvious incongruity with the clinical learning outcomes of the programme.

The need for a change – modifying the experiential pharmacology content

In 2018, after much effort petitioning to address this issue, our experimental pharmacology curriculum was finally revised and restructured to better suit the needs of the College and more importantly, to establish a new standard for responsible and relevant practices to teach undergraduate students about animal models of experimentation. Upon researching alternative experimental pharmacology curricula, it became evident that our college was not alone in the use of outdated material and experiments. None seemed to fit our vision of the skillset and corresponding learning objectives we wanted our students to attain. While alignment to the course and programme learning objectives was the main driving force in light of the clinical nature of the degree offered, we still felt it was essential to retain a practical component for animal models of experimentation given their importance in the development, validation and safety assessment of medicines.

Our new targeted learning objectives included:

- Introducing the use of animals in research in a structured and responsible manner.

- Understanding the importance of animal models in research in shaping and guiding the drug development and discovery process. We particularly focus on developing an appreciation that the welfare of the animal is directly linked to the quality and reproducibility of the experimental data generated.

- Developing awareness of the regulations and requirements needed for the ethical and responsible use of animals in research.

How the British Pharmacological Society’s Research Animals Curriculum inspired the changes to our lab curriculum

The British Pharmacological Society’s Animals in Research Curriculum provided a structured set of

core learning outcomes that echoed some of the essential principles we wanted to deliver within our experimental pharmacology curriculum. The material disseminated on the webpage were essential in helping to restructure our curriculum. More recently, the

Research Animals Sciences Education Scheme (RASES) has been launched to help support other academics to teach this topic.

Rather than emphasising the need for each student to simply acquire some animal handling experience that ultimately would not actually contribute to achieving any of our outlined course or programme learning outcomes, the new curriculum ensures that each student fully grasps the right way to conduct animal-based research. We impart a sense of responsibility and respect when it comes to exercising any animal handling practices. Where previously a very limited number of animals were available to effectively demonstrate an experiment to over 20 students at a time, now each student gets hands on experience using animal dummies ensuring that all students are more efficiently trained in a safe and stress-free manner. Furthermore, students’ understanding of experimental design is tested using case studies and objective structured practical exercise (OSPE) stations equipped with

videos hosted on the BPS core curriculum webpage including those from the

NC3Rs on correct animal handling techniques. These changes have aligned with both refinement and reduction of animal use.

In addition, we complement this experiential teaching and learning with organ bath simulation programmes such as those developed at the University of Strathclyde (OBSim and RatCVS). These programmes have played an indispensable role in increasing students understanding of drug response in tissues. With such measures we have effectively stopped the unnecessary waste of valuable animal resources and have shifted the focus of our sessions away from simple technical skill training to ensuring that students grasp an understanding of essential principles through a problem-based learning approach and active cognitive exercises.

My international training as an MSc and PhD student in the UK, coupled with the ability to source and utilise trustworthy teaching resources provided by the British Pharmacological Society has offered exposure to a number of exemplary practices that we attempt to incorporate to improve the standard of education we deliver to our students. The message we promote will hopefully inspire a new generation of healthcare researchers trained in ethical research practices and establish a culture of awareness and responsibility to uphold exemplary animal welfare regulations in research.

Getting it right – how we achieved programme alignment and responsible delivery

The new experiential component for our introductory pharmacology course provides a well-rounded and complementary variety of topics and learning exercises designed to expose students to a wide array of essential practical skills. We have adapted our experimental pharmacology curriculum to ensure that we achieve basic learning outcomes that are aligned with the course and programme learning outcomes aimed at training clinical pharmacists that are also competent in a research and scientific setting (see Figure 1). The vital role of animals in pre-clinical drug development and scientific research should be recognised and appreciated by all students pursuing clinical degrees. We have taken an outdated curriculum and modified it to deliver this skillset in a more responsible and structured manner, and to further incorporate skills necessary for applying pharmacology principles in a clinical setting.

Figure 1. Achieving alignment: aligning the learning outcomes and objectives through a wider range of taught skills. ANS: autonomic nervous system, CVS cardiovascular system.

Comments

If you are a British Pharmacological Society member, please

sign in to post comments.