Are all patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) are psychologically strong enough to endure the sudden onset of a chronic disease? Personally, my answer is no. I was not ready to face a chronic illness when I was diagnosed with Crohn’s disease at the age of 17, after 5 months of hospital tests, neither was I ready for 15 pills per day, and much more uncertainty.

Inflammatory bowel disease

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a group of disorders involving chronic, immune-driven inflammation of the digestive tract. There are two main types of IBD: Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis (UC). In Crohn’s disease, any part of the digestive tract can be affected, but only the colon and rectum are (superficially) inflamed in UC. According to Crohn’s & Colitis UK, Crohn’s disease affects about 1.5, and UC about 2.4, in every 1,000 people in the UK. An interesting epidemiological feature of both is their early appearance, usually between 10 and 40 years of age.

Symptoms

IBD involves flares (active phases with marked symptoms) and periods of remission (inactive phases with few or non-apparent symptoms), which are commonly seen with other autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis. The main symptoms of IBD are diarrhoea, tiredness, blood in the stool, weight loss and abdominal pain. These conditions can lead to intestinal obstruction, malnutrition, ulcers, and fistulas. Individual patients can also develop different symptoms, complicating diagnosis and requiring individualised treatment. As a disease of the digestive system, it might be considered that most symptoms are focused on the intestinal organs, but the reality is much more complex and unpredictable. In fact, in 2015, a clinical review affirmed that 50% of IBD patients will experience one or more extraintestinal manifestations (EIMs) in the course of their lives. EIMs can develop even before the diagnosis of IBD, which further complicates its detection and might aggravate the psychological distress in the patients. Musculoskeletal EIM is the most common extraintestinal symptom in IBD, and it can present in the form of peripheral arthritis, sacroiliitis or even ankylosing spondylitis. In addition, some of the EIMs follow an independent course from the intestinal activity, making the diagnosis and treatment even more difficult. Therefore, the view of IBD evolves from a digestive condition into a systemic disease.

The origin of IBD is unknown, but many factors have been suggested, such as genetic predisposition, environmental factors and even gut microbiome. IBD is a chronic pathology, without a definitive cure, in which the available treatments only alleviate the symptoms.

Treatment of IBD

As a cure for IBD is not available, current medicines focus on mitigating the symptoms and achieving and maintaining remission (defined as the disappearance of the symptoms, normalisation of the blood markers and complete mucosal healing). Given its heterogeneity in clinical presentation, talking about a unique treatment is impossible, but there are some commonly used medicines.

- Aminosalicylates and steroids are often used as the first treatment to target the inflammation.

- Immunomodulators are used as long-term therapy to modify immune response and reduce inflammation. They are useful to achieve and maintain remission.

- Biological therapies are indicated for those people with moderate-severe disease that is not responding to other drugs. These long-term therapies target proteins involved in the pathogenesis of IBD. This group includes anti-TNFα therapies, integrin receptor antagonists and interleukin-12 and -23 antagonists.

- Surgery is sometimes required to treat complications; for example, an intestine resection or an ostomy. However, surgery is not a definitive cure for the disease because the inflammation may reappear in other areas.

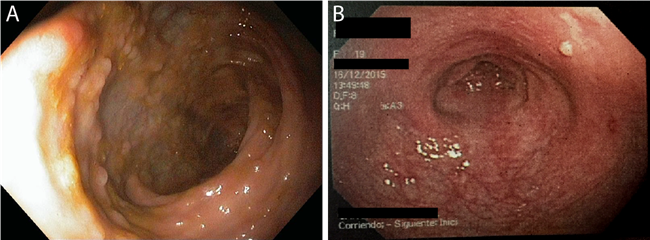

Figure 1. Results of anti-TNF therapy in one patient. (A) The intestine of a patient with Crohn’s disease, with the appearance of inflammatory signals and pseudopolyps before starting any treatment. (B) The intestine of the same patient 2 years after starting anti-TNF therapy. Most of the pseudopolyps have disappeared and there are still some remaining marks of the inflammation. The anti-TNF agent attaches to TNFα, one of the major proteins driving inflammation, and disables its interaction with the TNF-receptors, thus limiting the inflammatory signalling.

lthough these treatments are effective, they can cause multiple side-effects, such as Cushing’s syndrome, a condition caused by exposure to a high level of cortisol for a long period of time. The use of oral corticosteroids can produce an exogenous type of Cushing’s syndrome, characterised by weight gain, rounded face (moon face), stretch marks, acne, and thin, fragile skin. It isn’t only corticosteroids that lead to side-effects. As most of the therapies available modulate the immune system, patients are less able to resolve infections. This is the reason why, before starting a biological therapy, a tuberculin test is performed to detect latent tuberculosis that may progress into active tuberculosis. The patient's immunosuppressive status leaves them at high or moderate risk to develop complications for infectious diseases such as influenza and, more recently, COVID-19. In addition, the administration of live-attenuated vaccines such as the one for yellow fever are also contraindicated.

The psychological impact of IBD

Obviously, coping with a chronic illness can have a significant psychological impact, triggering depression and anxiety, especially common in younger patients. However, IBD forces sufferers to learn how to deal with it day by day, beginning a path of acceptance and improvement, which encompasses:

- Understanding their own body. Nobody else can feel the pain and understand the symptoms of an individual patient. Therefore, an introspective exercise listening to the body and mind is necessary to find their own needs.

- Responsibility. Meticulous control of medication is indispensable to overcome any disease but learning to respect their own limitations in each moment is probably the biggest exercise of responsibility.

- Social non-acceptance of the disease. “You don’t look sick” is probably the most-heard statement for an IBD patient. But what does a sick person look like? Being part of the invisible disease group, many people will not take IBD seriously.

- Individual self-fighting. Despite having relatives, friends, and professionals by their side, IBD patients face an individual, personal fight with their body. It is practically impossible to understand a disease that you do not have, even more so if it presents differently in each patient. IBD patients do not expect other people to understand their symptoms, they just need their support.

The importance of awareness

IBD is a chronic disease that appears at an early age and has no known cause or cure. Although current therapies significantly increase patients’ quality of life, they target the symptoms and not the underlying disease. Moreover, some patients lose response to the treatment eventually, affirming the necessity for more research to identify other therapeutic targets.

In psychological terms, patients are faced not only with the difficulties of a chronic disease but also with an ongoing drug treatment that can produce side-effects. IBD patients learn how to deal with a disease individually but relatives and friends still have an important role in this process. The investigation and treatment of IBD are work for professionals, but the comprehension, acceptance and the visibility of any invisible disease are in the hands of every one of us.

More from Editorial

Comments

If you are a British Pharmacological Society member, please

sign in to post comments.