Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease is a major health concern worldwide as it is one of the main conditions underlying dementia. Although various treatments have been developed to manage the disease, they are directed at alleviating the symptoms rather than tackling the pathophysiological roots of this condition.

Biogen recently developed a new drug – aducanumab (brand name, Aduhelm) to target the molecular basis of Alzheimer’s disease. However, the results of the clinical trials (221AD301 and 221AD302) are contradictory and therefore, its approval by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has split the scientific community into two opposing opinions: one side considering the drug as a remarkable step forward in Alzheimer’s research, and the other seeing its approval as a threat to the advancement of Alzheimer’s therapy.

How does aducanumab work?

To understand the controversy surrounding the approval of aducanumab, let’s first explore the features and mechanism of action of the drug, and how it differs from other Alzheimer's drugs.

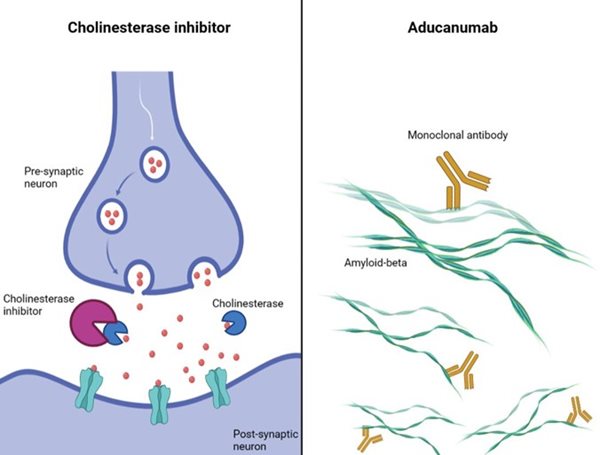

Previously developed drugs (for example cholinesterase inhibitors and glutamate regulators) aim to alleviate memory and cognitive symptoms, albeit temporarily, by targeting certain chemical processes occurring between brain cells (figure 1, left panel). Aducanumab, on the other hand, was designed to slow down the progression of the disease.

As a monoclonal antibody, aducanumab acts by binding to specific residues in the peptide chains comprising amyloid-beta (figure 1, right panel), to prevent it from accumulating and forming plaques in the grey matter of the brain (one of the principal causes of the disease).

According to cognitive assessment scales used during two Phase III clinical trials (221AD301 and 221AD302), aducanumab appeared to reduce cognitive and functional impairment in patients’ daily activities by decreasing amyloid-beta clumps.

Figure 1. The mechanism of action of one of the previously developed drugs for Alzheimer’s disease, a cholinesterase inhibitor (left) vs the monoclonal antibody aducanumab (right). Created with Biorender by Elisabetta Fato.

Previously developed Alzheimer's medications (for example rivastigmine) produce several side effects. The most common include nausea, vomiting, dizziness and fatigue. Less frequent but more concerning physiological consequences can include bradycardia and cardiovascular-related side effects, as well as rare cases of hepatitis and pancreatitis.

At present, the observed adverse effects following aducanumab administration include amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA), i.e. swelling in certain regions of the brain (sometimes accompanied by bleeding), vision changes, headaches and nausea. These symptoms originate from the dysfunctional blood-brain barrier but are generally temporary and manageable.

From discovery to controversy

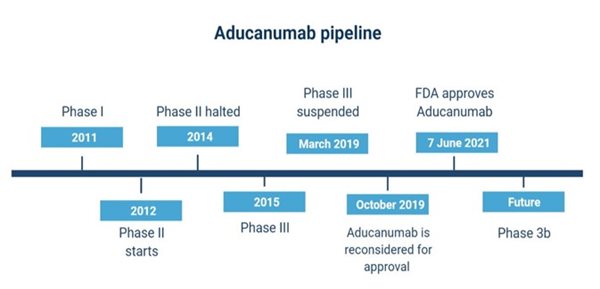

The path to development and approval of aducanumab has been complicated. It was discovered by Neurimmune together with a research team at the University of Zurich, then developed by Biogen and Eisai. Testing began in 2011 and the drug was administered to patients affected by mild Alzheimer’s in Phase I clinical trials. Phase III trials began in 2015, whilst the ongoing Phase II ‘EVOLVE’ study was ‘halted for futility'. Phase III involved two parallel, identical, double-blind studies (EMERGE and ENGAGE) testing aducanumab on patients with early Alzheimer's disease.

In March 2019, the studies were interrupted due to inconclusive results. However, in October 2019, changes in the statistical analysis of data gathered from one of the trials (EMERGE) showed positive results, convincing the FDA to carry on with considering the drug for approval, despite the parallel study (ENGAGE), not yielding such positive findings. The amyloid beta was more significantly reduced in the high dose-aducanumab group in EMERGE than in ENGAGE.

It is not surprising that a storm arose following the FDA approval of the drug on 7 June 2021 (figure 2), given the different outcomes of the phase III clinical trials, which will in fact be extended (phase 3b). One of the FDA’s own panels (the Peripheral and Central Nervous System Drugs Advisory Committee) opposed the approval, stating that the studies conducted had shown no significant evidence for the effectiveness of the drug.

The panel claimed it was the ‘worst drug approval decision in history’ and their opposition focused on the high expenses, false hope for patients, and the lack of real evidence for efficacy. The panel’s concerns about cost related to the administration of the drug itself, as it is injected intravenously once every four weeks by specialised nurses. They were also concerned about the cost of the positron emission tomography (PET) - an expensive imaging technique used after aducanumab has been administered to evaluate and monitor the state of amyloid-beta plaques.

Despite the high costs, adopting these follow-up measures could lead to a quicker advancement in biomarker development and has the potential to reduce costs for the diagnosis and monitoring of the disease in the long term.

Figure 2. A summary of the development and approval process of the drug. Created with Biorender by Elisabetta Fato.

Another argument in this debate is the negative impact that commercialisation of the drug could have on the future of Alzheimer’s research. It is mandatory that patients participating in ongoing or future clinical trials are informed about alternative approved and tested therapies and can choose to continue or quit the clinical trials. This could lead to the slower progression or even termination of clinical trials, causing companies to lose funds and resources.

Future perspectives on the use of aducanumab

No doubt newly developed drugs for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease represent a great step forward in the management of this neurodegenerative condition, which affected over 7 million individuals in 2017.

Considering that previous studies, which focused on drugs targeting beta-amyloid, were unsuccessful, if the effectiveness of aducanumab was more convincing, it would have been a revolutionary step forward in neurotherapeutics. However, there is still great debate as to whether the approval of aducanumab signifies more of an advantage or a disadvantage to the field.

At present, aducanumab is administered only in the US and is still undergoing review in most countries, where patients can have early access to the medication only in certain circumstances and through two programs: the Early Access and the Charged Managed Access, both for individuals with unmet medical needs.

For this reason, the FDA have demanded a post-approval clinical trial (Phase IV) to assess the long-term benefits of the drug. Currently, Biogen are conducting EMBARK (a Phase IIIb clinical trial) on the participants of the previous studies, to test the long-term safety and tolerability of the drug after a discontinuation period. EMBARK is due to complete in 2023.

As for most drugs, approval is never the destination, but only the first step in the journey of development and consolidation of advanced therapies.

Comments

If you are a British Pharmacological Society member, please

sign in to post comments.