Almost everyone nowadays knows about endorphins, brain neurotransmitters whose release is invariably invoked when someone is describing the sensation of pleasure. But few know that the first endorphins were isolated and characterised at the Unit for Research on Addictive Drugs (URAD) in Aberdeen, Scotland way back in 1975.

The story behind this groundbreaking scientific discovery begins many years earlier, when a young medical doctor, Hans Kosterlitz, fled the rise of fascism in Germany in the 1930s and settled in Aberdeen. For the next 40 years he taught and researched in physiology and pharmacology at the University of Aberdeen, latterly being appointed Professor of Pharmacology. He was highly respected for his meticulous research in the areas of carbohydrate metabolism and autonomic control of the viscera.

In the mid 1950s, Kosterlitz developed an interest in how opioid drugs, such as morphine, inhibited the function of autonomic nerves and how closely the effects he observed on peripheral nerves paralleled their actions in the brain; drug effects on isolated tissues are not complicated by pharmacokinetic factors such as absorption and distribution. However, in 1973 he would reach the age of 70, and for someone with his unbounded enthusiasm for research, retirement was never really a serious consideration. So, at a time of life when most academic scientists would long since have hung up their lab coat for the final time, Kosterlitz along with a young colleague, John Hughes, set up the Unit for Research on Addictive Drugs at Marischal College, an imposing granite building in the centre of the city. They obtained substantial funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (USA) as well as funding from the Committee on Problems of Drug Dependence (USA) and the Medical Research Council (UK) which enabled them to recruit a team of young scientists.

Marischal College, University of Aberdeen

This was already an exciting time in opioid research. Groups in the USA and Sweden had recently used radioligand binding to confirm the existence of specific opioid receptors in the brain. Hughes and Kosterlitz hypothesised that if there were specific opioid receptors, then there must also be an endogenous ligand that activated them. This hypothesis would now seem self-evident to any undergraduate pharmacologist, but in the 1970s it was a radical idea which they initially kept to themselves. To the amazement of the international scientific community, they and their collaborators isolated and characterised not one, but two endogenous opioid ligands - methionine- and leucine-enkephalin – both pentapeptides, from pig brain. They derived the term ‘enkephalin’ from the Greek kephalos to indicate that they were contained ‘in the head’. Subsequently, further endogenous opioid peptides were discovered by other research groups who coined their own names for their peptides (e.g. the dynorphins) and so to simplify what was becoming a diverse nomenclature, the doyens of the opioid field coined the generic term ‘endorphins’ to encompass all endogenous opioid ligands.

.png.aspx?width=550&height=275)

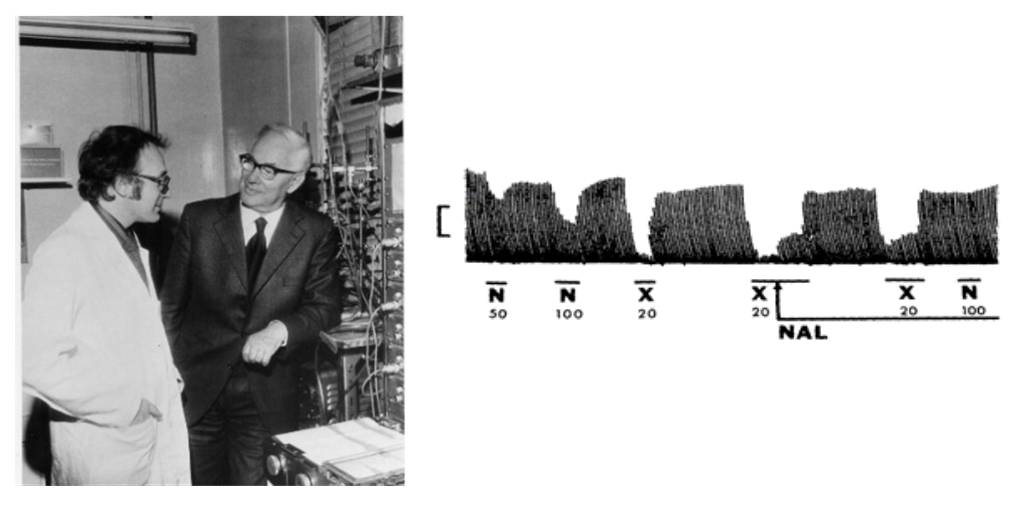

The photograph on the left shows Kosterlitz and Hughes discussing the latest bioassay results as they appeared on the polygraph trace. The original polygraph trace above shows the reversal by naloxone (NAL) of the depressant action of the brain extract (X) and the opioid agonist normorphine (N) on the nerve-evoked contractions of the mouse vas deferens [Reproduced from Hughes, J. 1975 Brain Res 88:295-308].

Why were the Aberdeen group successful in discovering the first endorphins? Undoubtedly it resulted from vision, self-belief, hard work and, as is frequently the case in science, a dose of serendipity. John Hughes had chosen to bioassay the brain extracts for opioid activity using the nerve-stimulated mouse vas deferens which his young PhD student, Graeme Henderson, had shown to be sensitive to opioid inhibition. Other possible bioassay approaches such as the guinea-pig ileum or displacement of opioid radioligand binding to brain membrane homogenates would have exposed the brain extracts to peptidases that would have degraded the small peptide enkephalins too rapidly for them to be assayed. It was highly fortuitous that such peptidases were not present on the extracellular surfaces of the nerves and muscle of the vas deferens. The discovery of the enkephalins undoubtedly changed the face of neuroscience.

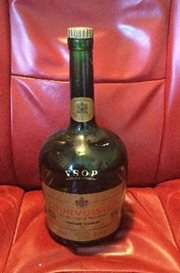

Not long after the paper characterising the enkephalins appeared in Nature, a wooden crate was delivered to the URAD laboratory. On its side was the ‘Harrods’ logo. Kosterlitz immediately demanded to know who had placed an order with this famous London store without asking his permission. However, his demeanour changed when, on finally managing to prise open the crate, he discovered a magnum bottle of Courvoisier brandy along with a note of congratulations from Sol Snyder, the eminent American neuropharmacologist at Johns Hopkins University, who had led one of the groups that pioneered opioid receptor binding. Unsurprisingly, the bottle has long since been emptied but remained in the proud possession of Sandy McKnight, an erstwhile member of URAD. Alistair Corbett has also kept a memento of his time in URAD - the actual polygraph shown in the picture of Hughes and Kosterlitz above - which for many years stood in the corner of his university office for students, staff and visitors to gaze upon. On his retirement, Alistair’s partner was less than pleased when he brought the polygraph home, insisting that it was not stored in the garage but displayed prominently in their new extension.

The gift from Sol Snyder

Following the discovery of the enkephalins, Kosterlitz and his colleagues went on to characterise the delta opioid receptor after they noticed that it required more naloxone to reverse the actions of the enkephalins than needed to reverse classical opioid drugs such as morphine, which were m receptor agonists. Over its lifetime, URAD produced 105 scientific papers, seven of which were published in Nature. The members of URAD worked hard, but none harder than Kosterlitz himself who, even in his 80s, would head straight to the lab from a transatlantic flight eager to hear what ‘new discoveries’ had been made in his absence. In URAD scientific discussions could be long and fierce but many a day ended with Kosterlitz buying the first beers in the neighbouring Kirkgate Bar.

URAD members by the graveside of Hans Kosterlitz in celebration of his life and the unit's founding.

On 27 April 2023, former members of URAD met in Aberdeen to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the unit’s founding. That precise day was chosen as it was also the 120th anniversary of Kosterlitz’ birth. In the morning they gathered at the graveside of Hans Kosterlitz and his beloved wife, Hannah, on an exposed hillside overlooking Aberdeen. Describing the foul weather, Alan North said ‘It wasnae just dreich, but gae oorlich’ and the photograph above, taken at the graveside, certainly illustrates the conditions. Later in the day, Graeme Henderson delivered the Kosterlitz Memorial Lecture to an enthusiastic and appreciative audience. He first recalled his time in URAD and the discovery of the enkephalins before discussing current controversies in opioid research and the dreadful problem today of high numbers of illicit opioid overdose deaths. Later in the evening, over dinner the former URAD members reminisced and shared anecdotes about the exciting and stimulating times they had spent working with Hans Kosterlitz, a man for whom they all have the utmost respect.

Hans Kosterlitz is a member of the BPS Hall of Fame in recognition of his services to pharmacology. Learn more about the Hall of Fame, and suggest your own Hall of Fame entries by contacting communications@bps.ac.uk

Comments

If you are a British Pharmacological Society member, please

sign in to post comments.