The careers of most academic pharmacologists follow linear pathways: typically, a BSc degree (possibly with a Masters), a PhD, a period of post-doctoral research training, then a lectureship and (hopefully) promotion through the ranks to professor. At each point along this pathway, many leave academia to follow alternative careers. In fact, most BSc graduates and just over half of UK PhD graduates leave higher education when they graduate. Although around 40% of PhD graduates remain employed in higher education after 3 years, only around one in ten of them will transition to a permanent academic post. While not common, some academics navigate a non-linear pathway, i.e. leave the linear path at some point to pursue a career outside higher education and resume an academic position later.

The ability to re-enter academia depends on the stage at which the person left, how long they were away from academia and what career path they followed. For example if a graduate realised that they had made the wrong career choice in the first year after obtaining a BSc, it may be relatively straightforward to register for a Masters or PhD programme and re-join the linear pathway to an academic career. On the other hand, if it had been many years since graduation and the experience gained was not of direct relevance to an academic position, returning would be difficult even with a PhD or postdoctoral training.

In this article, we outline the typical career paths of academic pharmacologists and then highlight some non-linear pathway options and funding streams that are currently available in the UK.

What does academic pharmacology look like?

Jordan contemplates different routes to academia. Art by Mariam Alakrawi, PhD student in cardiovascular sciences at the University of Manchester

Jordan contemplates different routes to academia. Art by Mariam Alakrawi, PhD student in cardiovascular sciences at the University of Manchester.

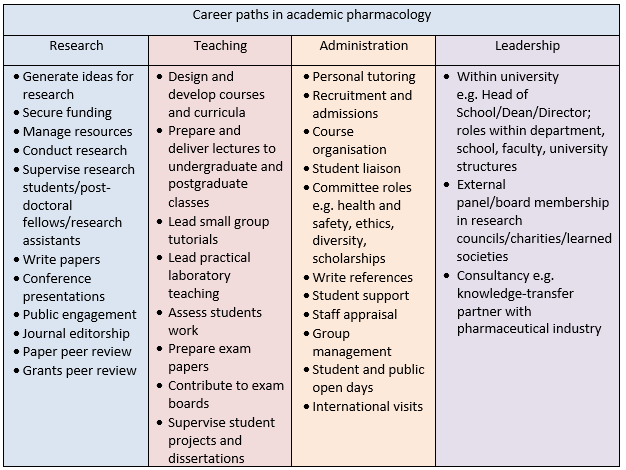

Roles in academic pharmacology traditionally combine research and teaching. Research-only posts are rare, so the best time to focus on research is during post-doctoral training. A key requirement of the job is the ability to secure grants to support research. Postdoctoral researchers can demonstrate their potential for this by applying successfully for fellowships that support their transition to an independent research programme. Academics are required to balance research, teaching, administration, leadership and societal impact (see table below for typical duties within these domains). Career progression depends on sustained achievements across these areas.

Teaching-focused lectureships offer an alternative academic career path, where the majority of time is spent teaching undergraduate and Masters courses, designing modules and curricula, recruiting and advising students, and on public engagement. A small proportion of time may be available for research, which is likely to be pedagogical. The career progression of teaching-focused academics is similar to that of academics on research and teaching contracts, with sustained achievements needed across all elements of the role and promotion through to professor.

A successful career in academia requires hard work, perseverance and resilience. Many consider research and teaching posts to be the most challenging, as academics constantly juggle writing papers and grant applications with teaching and responding to the needs of students. As only around 15% of grant applications are successful, a lot of work goes into building and sustaining a collegial, productive research team. Universities support academics by providing workshops on grantsmanship, strategic planning and internal peer review, but they also require their academics to be successful, because research is almost entirely funded through external grants.

What drives academic pharmacologists?

Academic pharmacologists are often motivated by the idea of leading ‘today’s science for tomorrow’s medicine’. Interaction with like-minded scientists at conferences and within academic networks fosters collaboration with an amazing international pharmacology community. Teaching talented and motivated students to be the next generation of scientists, pharmacists, doctors, nurses, and dentists can also be immensely rewarding and personally satisfying.

Why might people want to come back to academia from another career?

Academics expect their graduates to choose fulfilling and rewarding careers across many sectors, including healthcare, the pharmaceutical industry, scientific writing, specialist sales and technical advisors, biomedical scientists, clinical trials, project management, research funder administration, government advisors and academia. PhD graduates pursue careers across similar areas and may continue to employ and develop skills acquired during their academic studies. Although postdoctoral researchers have opted to follow an academic career path, the challenges of academic life and the paucity of positions available mean that the majority eventually seek an alternative path. However, many people leaving the academic pathway continue as professional scientists and retain an interest in pharmacological research and education.

Individuals may miss academic freedom, which is integral to academic life. For example, while academics choose what research to pursue, research in a pharmaceutical company is dictated by company strategy. It is important to be aware, however, that in order to do any research, the academic needs to find funding. Perceived job security is another reason that people choose to re-enter academia. Whereas redundancy is not uncommon in private industry, at least until recently, academic positions were seen as permanent. Pharmacologists may also have fond memories of life as a PhD student or postdoc, although they should be aware that the role of an academic pharmacologist changes as their career progresses, with less time available to spend in the laboratory and more time spent on project planning and supervision.

What are the barriers to a non-linear career pathway?

Academic positions are advertised internationally and the calibre of candidates is very high. For a research and teaching lecturer, recruitment panels look primarily for a strong track record in research, which should include internationally recognised publications and evidence of substantial grant or fellowship funding. A significant publication record is also necessary to persuade grant-awarding bodies to award funding, no matter how good the project seems. Candidates from non-academic sectors will find it difficult to meet these criteria.

For a teaching-focused lecturer, the key attribute is evidence of teaching experience and ability in higher education. Early career researchers in universities have access to teacher-training programmes through which they can develop the experience required for Fellowship of the Higher Education Academy. This can be an advantage when applying for a teaching position, but it is not usually a requirement, as on-the-job training is provided for new university lecturers. Unless an applicant has had experience in a training or education role, they will find it difficult, however, to compete with candidates experienced in university teaching. On the other hand, fresh ideas about teaching approaches and curriculum development to incorporate new science are also important and can be demonstrated by applicants from outside academia.

What can universities do to facilitate a non-linear pathway to academic pharmacology?

The good news is that there are several non-linear pathways active in many universities. In some areas, professionals from outside academia are recruited to lead particular areas of the curriculum, (eg pharmacy practitioners) or to develop aspects of research (eg commercialisation). An alternative is partnership between industry and academia, with the working week split between the two employers. This model works UK-wide for clinical academics working in universities and the NHS; in the authors’ institutions, partnerships between industry and academia work well.

There are several funding streams available that foster collaborative working between universities and industry, such as the UK Research and Innovation Future Leaders Fellowships. Funding schemes are also available to facilitate a return to academia, such as the Wellcome Trust’s Research Career Re-entry Fellowships and the Daphne Jackson Trust’s Fellowships. As well as providing research training, good PhD programmes also develop core professional skills and run courses on career planning and management, which may include advice on non-linear paths to academia. The University of Manchester has an online resource that sets out the pros and cons of different routes. Queen’s University Belfast has a dedicated online resource for researchers with useful links to support and information.

Think about it!

If you decide that academia is for you, then go for it! Academic pharmacologists are enthusiastic about science, passionate about teaching, excited by curiosity-driven research and motivated by translational bench-to-bedside impact. The road may be difficult, but it is rewarding. Along the way, take advantage of resources such as mentoring schemes, which can link you up with a like-minded scientist. Most universities have mentoring schemes and national programmes are run by the Royal Society, the Academy of Medical Sciences and other societies. Information on mentoring is available through the British Pharmacological Society, which is a supportive, forward-thinking body that continues to drive innovation and discussion on the future of pharmacology in both academia and other areas.

Comments

If you are a British Pharmacological Society member, please

sign in to post comments.