‘A trip to West Africa: Gabon’s indigenous psychedelic’ is the winning article from the 2023 ECP writing competition. Authored by King’s College London student Jade Pullen, the judges enjoyed this topical article, and her mindfulness of the people impacted by its harvesting.

The rise of psychedelic drug research occurring around the world is nothing short of meteoric. Compounds such as psilocybin (active ingredient in “magic mushrooms”) and MDMA (ecstasy) are two such stars of the show, both currently in clinical trials for treating mental health conditions such as depression and PTSD. LSD (acid) may be another familiar name, whose synthesis by chemist Albert Hoffman in 1956 and subsequent escape from the lab was one of many catalysts blamed for the succeeding War on Drugs. This led to a suppression on research, which had initially shown great promise at treating psychiatric conditions. However, this research has been rekindled in recent years, an era dubbed the “psychedelic renaissance”, and scientists are once again looking to these compounds to help deal with a growing global mental health crisis.

Substance use disorder is another mental health condition, with more than a quarter of a million UK adults in contact with drugs and alcohol services between 2020-2021, not accounting for the numbers of people who have not sought treatment. The psychedelic compound tipped to treat these patients specifically is ibogaine, a powerful psychoactive substance that can be found in the roots of Tabernanthe Iboga, an evergreen shrub part of the Apocynaceae family. To locate this plant, you’ll have to venture to the equatorial rainforests of West Africa and visit Gabon, where it grows most abundantly.

Fig 1. The whole Iboga plant, found in the rainforests of Gabon. Photo: Google

There it plays an important role in the spiritual practice of Bwiti amongst indigenous tribes, who ingest the root either raw or ground up as part of ceremonies and healing rituals. This induces hallucinations and dream-like states, through which the recipient is said to receive deep insights and work towards healing any mental maladies.

Use of this plant is said to date back thousands of years, with the Bwiti traditions and beliefs being built solely around its powerful effects. It was in 1901 that French scientist Edouard Landin isolated the alkaloid ibogaine from the shrub and some research began into its potential as a medicine for the rest of the world.

Fast forward to the ‘60s, when American researcher Howard Lotsof, himself addicted to heroin, discovered that after taking ibogaine his cravings all but disappeared. Further research began in earnest to investigate claims of it being an “addiction-disrupter”. A 2022 review of clinical trials up to 2020 found ibogaine to be an effective treatment of substance use disorders. However, it did highlight caution in patients with cardiac conditions, due to two deaths in the studies reviewed. One of its unique selling points is the fact that single doses appear to have lasting impact, reducing the need for repeated treatments. One review of literature reported 30% of patients receiving ibogaine treatment for opioid addiction never touched opioids again. This is comparable to results with existing opioid replacement therapy drugs such as methadone or buprenorphine. However, these drugs achieve their results after lengthy detoxification processes in conjunction with regular counselling services, highlighting the appeal of a potential one dose treatment. Interestingly in the UK, ibogaine is not listed under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 (despite being a Schedule 1 drug in the US) but is instead classified as a medicinal herb. This has allowed a clinical trial to begin in Manchester, with a focus on treating opioid use disorder.

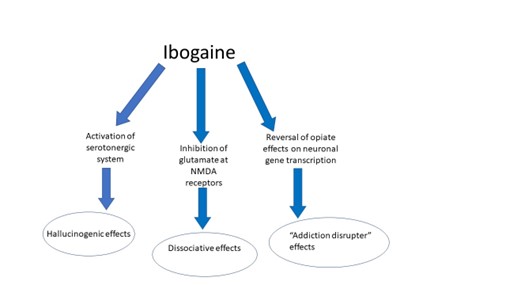

Ibogaine is a tryptamine and has a complex pharmacological effect on the central nervous system, in that it simultaneously triggers a variety of neurotransmitters in the brain. The hallucinogenic effects are thought to arise from action on serotonin receptors, whilst inhibitory actions at receptors for glutamate (the body’s main excitatory transmitter) give rise to the dissociative effects reported. With guidance from a therapist, these states can help a patient access repressed trauma and reveal indications regarding the root causes of their addiction. Although not well understood, its apparent capability to interrupt addiction may lay with its effect on neuronal opioid receptors. These are indicated in behavioural rewarding and reinforcing pathways, and ibogaine appears to have an adaptive influence on them, effectively returning neurons to the condition they were in before addiction took hold. Ibogaine is cleared from the body relatively quickly, but its active metabolite, noribogaine, is detected in plasma for days after initial dosing. Noribogaine’s slower clearance has been linked to the reported long term beneficial after-effects on cravings and mood.

Fig 2. Effects of ibogaine on the CNS. Other neuronal pathways may also be implicated and require further investigation.

Although this Western adoption of ibogaine is proving useful to many people suffering, its appropriation has not gone without adversely impacting the Gabonese culture and environment. The ever-increasing demand for its root source has meant supply has been stripped unsustainably from the forests, and locals are going without their precious medicine. Poachers wreak havoc on the flora and fauna in their attempt to get hold of the plant to sell on the black market, and deforestation has destroyed wildlife habitats. The discussion around indigenous reciprocity has been a source of contention, as the tribes that have closely protected these plants have been left out of profits made by foreign companies from ibogaine.

Thankfully, steps have been taken to protect these tribes’ livelihoods, and ensure a sustainable supply of iboga can be maintained. Under the Nagoya Protocol, reciprocal relationships are being formed between companies making money from ibogaine and the local tribes tending the iboga crop. This international legislation has the aim of “sharing the benefits arising from the utilisation of genetic resources in a fair and equitable way” and many projects are underway to ensure this happens.

Ibogaine is a fascinating and interesting compound, showing much promise in clinical applications with treatment resistant addictions. The concept of healing through insights and visions is not unique to ibogaine as a psychedelic, but its physiological effects on the nervous system seem to lay at the heart of its anti-addictive properties. As with much of this research, more is needed to fully understand its mechanism of action and safety measures to prevent any serious medical complications.

However, the case of ibogaine highlights the responsibility we have, as scientists, to acknowledge the origins of the compounds and medicines we are studying and respect the long-standing heritages that surround them. It is a privilege to be able to study these molecules and we must give thanks to the indigenous knowledge that has allowed us to utilise them. Our planet’s resources are not infinite, and in our rush to treat our ills, we must also make efforts to protect nature and create sustainable environments to see us all into the future.

Comments

If you are a British Pharmacological Society member, please

sign in to post comments.