School of Pharmacy, Bloomsbury Square at the time I studied there (1952-55)

My introduction to pharmacology was, in the 1950s, as a student at the University of London School of Pharmacy then located at 17 Bloomsbury Square, an attractive building which even had an Adam ceiling in one laboratory. There was a strong tradition of pharmacology at ‘the Square’. Previous famous pharmacologists who had worked there included Josh Burn (later Professor at Oxford) and John Gaddum (at Edinburgh). It was hearing a lecture by the latter in 1954 that led me into pharmacology. The Department of Pharmacology was a happy one, chaired by the kindly and generous Professor Gladwin Buttle.

The supervisor for my PhD was the newly appointed Reader: Geoffrey West from Dundee. There, he had discovered, with James Riley, the location of histamine in mast cells. We showed that, in some species, these cells also contain 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT). Geoff was keen that we communicated our findings quickly and so this was at meetings of the Physiological Society because, unlike the BPS at that time, it met four or six times a year and the abstracts and the subsequent papers were published: as mine were in 1956 and '57.

My first meeting of the BPS was in 1956 at Mill Hill and my initial oral communication was at the 25th Anniversary meeting in Edinburgh that same year. Little did I know then that later Scotland would become my workplace and our family home. My initial publication in the BJP (the first of about eighty in our illustrious journal) was in 1958.

In those days the BPS was more like a small club with only about 200 members. Geoff was good at introducing his research students to the eminent pharmacologists of the day such as the great Sir Henry Dale who earlier had written an autobiography of his ‘adventures’ (Dale 1953), which I still possess. Anyone with an interest in ‘autopharmacology’ will find this book fascinating. After shaking hands with Dale in 1956 I was reluctant to wash my hands for several days!

In the 1930s Dale had invited several pharmacologists from Germany to work with him at Mill Hill and many stayed to become the backbone of the Society. Among them was Wilhelm Feldberg who, with both Burn and Gaddum, had worked with Dale in the 1930s on chemical transmission. Feldberg, who had published a book on histamine in 1930, was the examiner for my PhD oral. Geoff West, in preparation for the viva, had placed on the table Feldberg’s favourite cigars! Was this I wondered a Scottish tradition during his days in Dundee? And did it contribute to the success of the oral?

Not many of the present BPS membership would remember what it was like to live and work in London during the 1950s, just a few years from the end of WW2. Bomb damage was still apparent, there was still rationing and the smoggy atmosphere in winter meant it was sometimes difficult to see where you were going.

The next step for me was to move to Bristol to study medicine but a notice in the Pharmaceutical Journal instead prompted me to apply for a lectureship at the newly founded School of Pharmacy in Ibadan, Nigeria. This College was under the sponsorship of the UK Council for Overseas Development. I was offered a Senior Lectureship in pharmacology with a starting salary on a scale of £1524-2176, with first class airfares and three months annual leave and with accommodation provided. So it was that in 1958 and at the age of just twenty-four I found myself responsible for the curriculum, for teaching and research in a newly established department and in a new country.

All this was good experience for thinking ahead since drugs and equipment had to be ordered well in advance to account for the distance and time involved in travelling the three thousand miles from the UK to Nigeria – three weeks by boat, then clearance through customs and the hazardous road journey from Lagos to Ibadan. No telephone or online connections in those days.

.png.aspx) L: First staff of the School of Pharmacy, Nigerian College, Ibadan (1958) The other pharmacologist was Max Foy to the left of the group. R: In my first research lab, Ibadan 1958. This equipment (smoked drum, organ bath) is now in a museum.

L: First staff of the School of Pharmacy, Nigerian College, Ibadan (1958) The other pharmacologist was Max Foy to the left of the group. R: In my first research lab, Ibadan 1958. This equipment (smoked drum, organ bath) is now in a museum.

It was important to begin some kind of research and, with my other staff member Max Foy (later of Bradford University) we began by discovering the presence of 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) in a variety of tropical fruits like the pineapples and bananas growing in the family garden. A few years later I noted the geographical similarity between the peoples that ingested large amounts of plantain and ‘matoke’ bananas (rich in 5-HT) and the occurrence of an unusual cardiac disease called endomyocardial fibrosis. This led to the finding that such patients have a markedly reduced ability to handle ingested 5-HT, which can be cardiotoxic (Ojo and Parratt 1966).

After three years at the School of Pharmacy I moved in 1961 to the nearby Department of Physiology of University College Ibadan. UCI was one of three universities set up in the former colonies after WW2 by the UK government. This story has been told by its former first Principal Kenneth Mellanby (Mellanby 1958). The move to the Medical School at UCI was a good one. The department had an interest in the measurement of tissue blood flow and this began, for me, a lasting interest in the coronary circulation and its regulation under pathophysiological conditions. I think I must be the only pharmacologist who has attempted to measure myocardial blood flow in a hyena: donated, because of ‘bad behaviour’ by the university zoo. Much of this research was published, in many publications from 1964 onwards often in the BJP.

How to summarise almost ten years living and working in Africa? The attractiveness of the Ibadan campus with the opportunity of teaching, in small classes, the best medical students in West Africa; that dangerous ninety mile Ibadan Lagos Road which we had to undertake each month in the early days for our shopping; an encounter at dusk with an angry dangerous bush cow on a remote laterite road which put our car out of action; the two military coups which led ultimately to civil (Biafran) war; my attacks of malaria and (more dangerous) of dengue; the sun and heat and those many lasting friendships.

Positions at UCI were only temporary for expatriates. The University was waiting for Nigerians to return, following postgraduate studies in the UK or USA. So how was I to return to a position in the UK or elsewhere? Then in 1966 and ‘out of the blue’, on a blue airmail letter, I received an invitation from Bill Bowman (later an Honorary Member of the BPS and General Secretary of IUPHAR) to join him at the new Department of Physiology and Pharmacology at Strathclyde. Despite invitations, to move to London and elsewhere, I remained in Glasgow until I ‘retired’ in 1998.

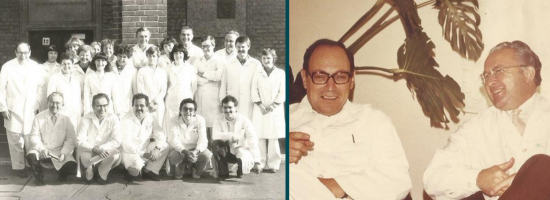

The cardiovascular research group University of Strathclyde almost fifty years ago.

The cardiovascular research group University of Strathclyde almost fifty years ago.

Within a year of moving to Glasgow in 1966 I received two invitations that were to change the course of my scientific life. The first of these was to join the Glasgow University Department of Surgery at the Western Infirmary who had a group working on coronary blood flow regulation. I was joined there over the next ten years by a succession of PhD students including Dick Marshall, Susan Coker and Cherry Wainwright. This led to a deep interest in disorders of cardiac rhythm and their treatment by drugs, the coronary vascular effects of working at 2 and 3ATA in one of the hyperbaric chambers, and in the phenomenon of preconditioning. During my time in the Department of Surgery there was increasing concern about the high mortality of patients who developed septic shock especially after bowel surgery. This concern led to the formation of a group within the department set up to investigate how to deal with this clinical problem. My task was to examine the potential contribution of bacterial endotoxin. This involved the participation of other members of the Strathclyde Department especially Brian Furman and Ian Rodger. Later, with grants from the EC, we joined Jean-Claude Stoclet and his group in Strasbourg to investigate the important part nitric oxide plays in the cardiovascular disturbances of sepsis,

The second invitation came from such an unlikely source that I was tempted to ignore it. It was another letter ‘out of the blue’ this time from Laszlo Szekeres working in Szeged, Hungary. He suggested that, our research interests being similar, we collaborated including an. exchange of staff, unusual during communist times. This led to me working in Szeged many times during the ‘cold war’ period and, when I retired, to living and working there, supported by a grant from the Leverhulme Trust and the award of the Szent-Gyorgyi Fellowship from the Hungarian Government. My final publications, including some in the BJP, came from there in 2006, fifty years after my first.

.png.aspx) L: The Department of Pharmacology Szeged Medical School in about 1970. Note the formal 'dress'! R: With Laszlo Szekeres in Szeged, Hungary in 1975.

L: The Department of Pharmacology Szeged Medical School in about 1970. Note the formal 'dress'! R: With Laszlo Szekeres in Szeged, Hungary in 1975.

Another consequence of the early Hungarian connection was my frequent visits during the communist period, from 1973 onwards, to laboratories in other countries in Eastern Europe. An account of these visits is outwith the scope of this article but is recorded in my memoirs (Parratt 2021). Such visits were joyful, sometimes sad and often potentially dangerous. However, these contacts led, after the fall of communism in 1989, to the set up of a long-term EU supported European wide network on cardioprotection which I was privileged to chair, the highlight of an adventurous, richly rewarding life in pharmacology.

I realise that in my 92nd year these reflections may not be especially helpful in the 2020s to any budding pharmacologists. Except perhaps for this: none of the above could have happened but for the intervention and advice of the only woman on the staff of the department of pharmacology at the ‘Square’. Three months into my PhD I was about to give up; things were just not working out. Dr Monica Mann persuaded me to continue and so all the above adventures followed. But for that intervention it could have been so different. What I would have missed!

So, ‘carry on’, persevere. You will get there. And, to a good place.

References

Dale, HH (1953) Adventures in physiology. The Welcome Trust, London,UK

Mellanby,K. (1958) The Birth of Nigeria’s University. Methuen, London

Ojo,O and Parratt, JR (1966) Lancet i, 854-856

Parratt, JR (2021) A Scent of Water, Handsel Press, EdinburghComments

If you are a British Pharmacological Society member, please

sign in to post comments.