"You are not going to Yobe. I don’t mind you waiting for the next batch." This was my father’s response as I told him over the phone that I had been drafted to Yobe state for my National Service. I like to think myself an obedient son, but as my dad himself must have known, this wasn’t his decision.

It was in the early weeks of 2017. Lagos was returning to its normal frantic pace, following a reluctant break in December. It was cold and dry, and the dusty January harmattan winds eased across the crowded neighborhoods. I had completed my 1-year internship in August the previous year at the National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control (NAFDAC). The internship was mandatory for full registration as a Pharmacist by the Pharmacists Council of Nigeria. After working in three different directorates during the period, I got involved with the Drug Demand Reduction Unit at the tail of the program after the deputy head of the unit happened to see an essay I had written on drug addiction and stress. She co-opted me and I continued to volunteer after my internship ended. I helped set up monitoring and evaluation frameworks for the activities that were conducted within the unit, including sensitisation programs undertaken at schools, religious houses, and professional and trade groups.

National Youth Service Corps

The National Youth Service Corps was the critical next step, without which a graduate cannot be employed in Nigeria. The program was established by the then military head of state, General Yakubu Gowon, following the 30-month fratricidal civil war in 1967–70. The scheme aims to, among other things, improve the nationalism and patriotism of university graduates by helping them experience first-hand different cultures in Nigeria. Those on the scheme are referred to as Corp members or colloquially as ‘Youth corpers’.

Yobe state

I hurriedly packed, said my goodbyes and raced to the bus station. After 24 hours and over 30 military checkpoints later, we arrived at Potiskum, Yobe state in North-Eastern Nigeria. This is the region where the deadly terrorist group Boko Haram began in 2002. In Yobe, Borno and Adamawa states, the terrorist group established a triangle of terror that occasionally spilled into neighboring states. The gruesome attack on Federal Government College Buni Yadi, which claimed the lives of fifty-nine students in February 2014, and the July 2013 attack on a state-run boarding school in Mamudo, which killed at least 42 people, were some of the darkest episodes of violence in Yobe state. In 2014, several states, including Yobe, were excluded from receiving Corp members as a result of the violence. My batch was the first to be drafted to the State after the exclusion in 2014.

Physical drills during the camp

The town looked ravaged and the rigors of war were noticeable from the lack of nightlife, numerous military checkpoints, charred and abandoned buildings and above all a perceptible fear. These aside, the locals were very welcoming. My very first act on alighting from the vehicle was to get some suya and balangwu – spicy local preparations of beef – from a roadside vendor. This was to be my home for 3 weeks, a home I was to share with over 2,000 Corp members, many army personnel, as well as personnel from other security and para-military forces.

We had a parade early the next morning, after which I reported to the camp clinic to work as a Corp pharmacist. It was a lesson in resource allocation and priority setting for the fledgling medical team, which included only two experienced nurses. Medications were in short supply and patients were in abundance. The harsh harmattan was a factor: the chilly northeast trade wind swept across the Sahara bearing tiny particulates. As we struggled to deal with these, we had no idea that something else was brewing within our ranks.

Cross section of camp clinic staff (author is second from right)

Problems within the ranks

In a gathering of young people from all over the country, one would expect that there would be issues with drug use. We were aware that somehow, drugs (including marijuana and prescription drugs) and alcohol had filtered into the camp even though movement was restricted and Corp members were not supposed to be allowed out of the camp without authorisation. In the second week of the camp, we saw the troop formations change. It wasn’t apparent why this happened and we were never told, but we theorised at the time that it was due to a terrorist attack within the state, as some news report suggested. The soldiers were suddenly apprehensive and routines changed.

People began to approach me about getting prescription drugs, since I worked in the camp clinic. I got into a sincere conversation with one of them and he told me about his struggles with drug use and how he had had to go overseas for ‘detoxification’ and was dealing with some kidney issues, which he did not disclose. Two days later, he was rushed into the camp clinic, having just passed out. He woke up agitated and screaming, so much so that he had to be restrained. Based on our conversations with him, we believed this to be a withdrawal symptom. He was later taken to a hospital in the state capital.

Corp members after a parade drill (author is fourth from left).

An opportunity to learn and help

This incident got me thinking about how important it would be to have concrete data on drug use among graduates. The camp, made up of young graduates from all states of the country, seemed quite representative. Despite very poor internet access in the area, I did some background research. I discussed the issue with other members of the medical team and we presented a proposal to the camp coordinators that we talk about substance abuse with our fellow Corp members and distribute a questionnaire for research purposes. They agreed.

We held the presentation in a large tent that was used for lectures. There were lots of questions, and one could tell that there was a genuine interest in the subject. We distributed the questionnaires and encouraged the Corp members to respond as honestly as possible. The questions continued to come for days after the presentation. I was approached by a number of Corp members afterwards, seeking help for themselves or for others. We gave them some helpful advice and provided them with the contact details of operational treatment centres.

After the camp

At the end of the camp, members of the camp clinic were presented with letters of commendation from the State NYSC Authorities, partly because of this project. I was redeployed to Lagos state, where I had a job waiting in Drug Demand Reduction.

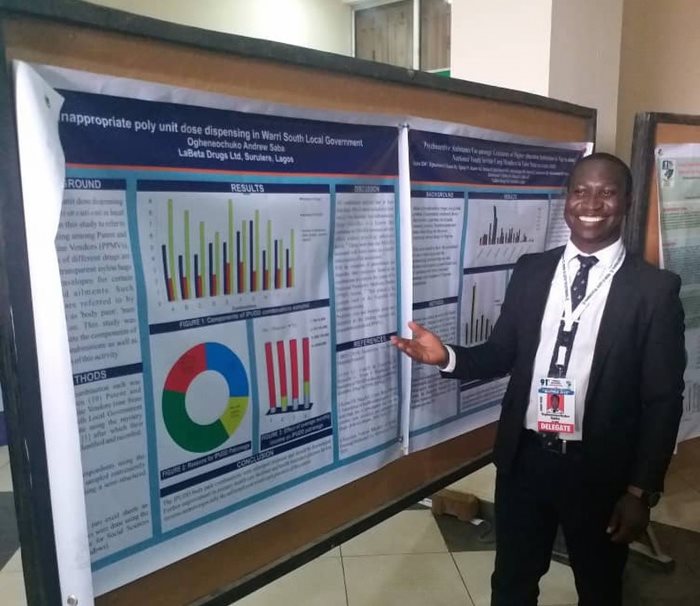

My colleagues and I compiled the report and sent it to the authorities of the state in which the study was conducted. I was referred to submit it to the authorities in Lagos, those in charge did not seem interested. We eventually presented our findings as a poster at the Pharmaceutical Society of Nigeria Conference in 2018.

Poster presentation at the Pharmaceutical Society of Nigeria Conference 2018 at Ibadan, Nigeria

My experience in Yobe shaped my career in many ways. My current foray into public health is born out of my desire to understand substance misuse and to explore possible solutions.

Comments

If you are a British Pharmacological Society member, please

sign in to post comments.