Morphine is sometimes prescribed in France to some opioid-dependent patients who are insufficiently relieved by or intolerant to validated substitute treatments (buprenorphine and methadone), without any analgesic indication. The feasibility and tolerance of this therapeutic option is demonstrated by international clinical studies for oral administration. However, real-life care does not allow for such strict control over the delivery of the drug. Several field surveys and postmarketing alerts have reported frequent diversion of oral galenic for intravenous administration, with high doses delivered.

In the

context of the global opioid crisis, this use of morphine as a replacement for validated treatments may seem worrying, as the extent of the practice and its potential risks are unknown. However, analysis of French health insurance databases has provided some answers.

Over a period of nearly 3 years,

my research team sought to compare the 1-year incidence of overdose, death, drug misuse behaviour, and complications associated with intravenous injection between patients prescribed morphine for opioid addiction and those prescribed a conventional substitute.

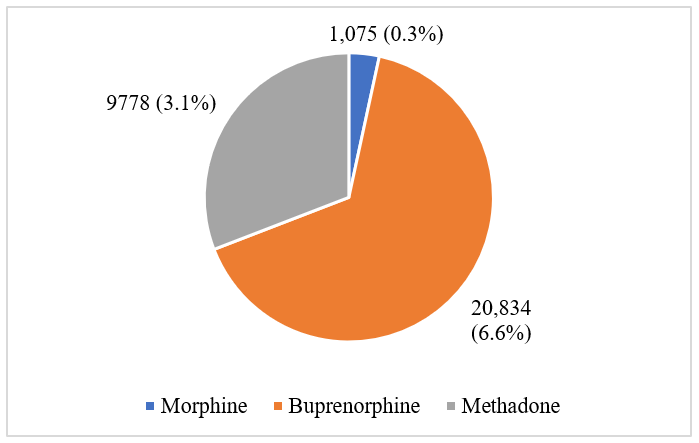

Only 3.4% of the 31,687 patients who initiated management of their opioid dependence received morphine (Figure 1). These patients showed increased socioeconomic precariousness, with more infectious, psychiatric, and addictive comorbidities than patients receiving conventional treatments. Patients receiving morphine also had an increased risk of overdose within a year of starting treatment and higher incidences of death, doctor shopping and bacterial infections (see table). There were no significant differences in the incidences of HCV and serious thrombotic complications.

Although marginal compared with validated treatments, alternative morphine use in opioid dependence is a risk factor for serious complications because of the diversion of oral galenic for intravenous administration. Given their numerous comorbidities, these complex patients, paradoxically only followed by general practitioners, would benefit from multidisciplinary management within specialised addiction unit. These structures would allow physicians to manage the comorbidities, prescribe emergency naloxone kits to fight the overdose-death risk and provide free sterile injection kits to limit infectious and thrombotic complications.

It can no longer be ignored that some patients are not sufficiently relieved by the substitute treatments or by the recommended routes of administration. Is it appropriate to continue to prescribe to these complex patients an off-label treatment whose route of administration is known to be at high risk of diversion? Why not propose an injectable substitute, which could be self-administered under medical supervision in

lower-risk consumption rooms? This framework would make it possible to gradually offer patients a multidisciplinary care approach, including social workers to combat their precariousness, but also the screening and management of infectious and psychiatric comorbidities and therapeutic education for the prevention of overdoses.

Figure 1.

Figure 1. Number of opioid-dependent patients included in each cohort

Table. 1-year incidence of risks assessed in the morphine cohort versus conventional treatments

| Risk factor |

Morphine cohort |

| v buprenorphine |

v methadone |

| Overdose |

x 3.8 |

x 2.0 |

| Death |

x 9.1 |

x 3.9 |

| Doctor shopping |

x 2.9 |

x 66.8 |

| Bacterial infections |

x 2.8 |

x 3.6 |

| Hepatitis C seroconversion |

x 1.6 (NS) |

x 1.1 (NS) |

| Thrombotic complications |

x 1.4 (NS) |

x 1.3 (NS) |

NS: statistically insignificant result

More from Young pharmacologists

Comments

If you are a British Pharmacological Society member, please

sign in to post comments.