Marco Bonfanti, University of Strathclyde, is the first runner up from our annual writing competition for early career pharmacologists. Marco’s submission ‘psyched for psychedelics’ was selected by judges for its topical theme, connecting science and society.

For each writing competition, we look for exceptionally written and well-communicated science on any pharmacology-related topic. Each of our entries was scored independently by a panel of judges*.

For more than 5,000 years, humans have consumed psychoactive substances for religious, medical, and recreational purposes. Psychoactive drugs act mainly on the brain and can be classified into four groups: depressants, stimulants, opiates, and hallucinogens. Some drugs, like benzodiazepines, cause depressant responses and are useful to treat anxiety. Others stimulate the brain, like caffeine, increasing focus and aiding concentration. Opiates are a different kind of depressant and also have pain-relieving properties. Hallucinogens, or psychedelics, cause distorted perceptions and have been commonly believed to have no clinical use. However, some members of the scientific community are exploring an important question: is the stigma around these drugs justified?

From Woodstock to the psychedelic renaissance

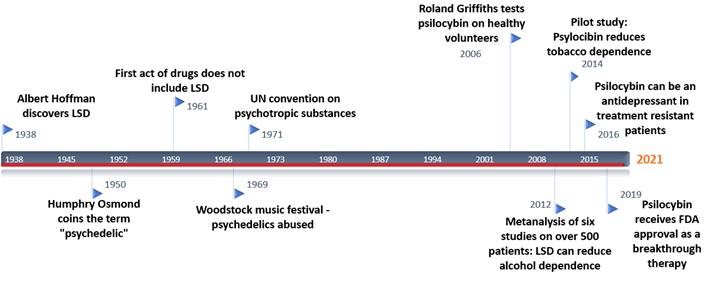

During the 1960s, psychedelics gained great popularity amongst young adults and became one of the symbols of the hippie movement. The widespread abuse of Lysergic Acid Diethylamide, commonly known as LSD, led the United Nations to call the convention on psychotropic substances in 1971. Psychedelics were labelled ‘Schedule 1’ drugs – a serious risk to public health with no therapeutic use. Due to these severe restrictions, psychedelics research has lain dormant for decades. Only in recent years have scientists reawakened interest in these molecules. The psychiatrist Ben Sessa named this new era the ‘psychedelic renaissance’.

The magnifying glass of psychiatry

In the early 1950s, British psychiatrist Humprhy Osmond coined the term ‘psychedelic’. It derives from two Greek words – ‘psychē’ (which means ’soul’ or ’mind’) and ‘dēloun’ (which means ’to show’ or ’to reveal’). Some people consider psychedelics as ‘mind-opening’ drugs, compounds that can ‘reveal one’s consciousness’. Because of these mind-opening properties, the Czech Psychiatrist Stanislav Grof compared the significance of psychedelics in psychiatry to the microscope for medicine, or the telescope for astronomy in his book ’Realms of the human unconscious’.

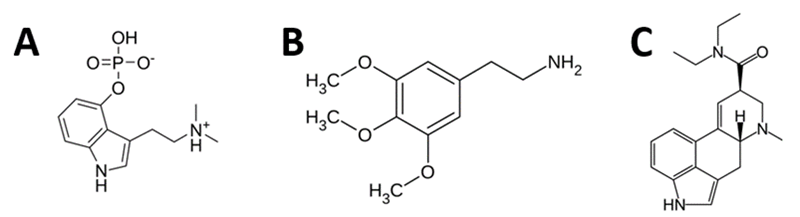

The three most famous psychedelics are:

- Psilocybin, found in more than 200 species of fungi, often referred to as ‘magic mushrooms’

- Mescaline, the psychoactive compound of the peyote cactus, used in shamanic rites in Latin America

- LSD, first synthesised from rye fungi in 1938 by the Swiss chemist Albert Hoffmann.

Other compounds such as 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) and ketamine may provoke hallucinations and are sometimes referred to as psychedelics. However, they activate a wide range of pharmacological targets, as opposed to psilocybin, mescaline, and LSD, which share similar mechanisms of action.

Figure 1. Chemical structure of the three main psychedelic molecules. Psychedelics can be found in nature, such as psilocybin in ‘magic mushrooms’ of the Psilocybe genus (A) and mescaline in the peyote cactus Lophophora williamsii (B), or can be synthesised like LSD (C).

Many substances, one receptor

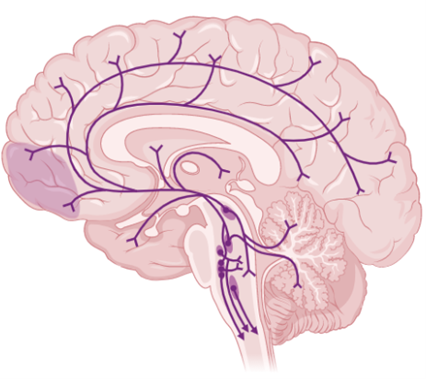

In the brain, psychedelics interact with the serotoninergic system: a series of connected neurons that share the ability to produce serotonin, or 5-hydroxytriptamine (5-HT). Serotonin binds to a great variety of receptor subtypes and to date, 13 have been discovered. Psychedelics activate the 5HT2A receptor and in doing so, they can cause hallucinations. So, can a hallucinogen be a useful medicine? There is some research into the clinical role of the 5HT2A receptor and how it is involved in synaptic plasticity – or how neurons associate and dissociate synapses, creating memories and facilitating learning.

Figure 2. The serotoninergic pathway in the brain. Neurons in this network secrete 5-hydroxytriptamine (5-HT). This pathway is involved in a variety of physiological functions such as motor activity, food intake, sensory processing, emotional processing, and mood. Image created with BioRender.com.

In the brain, specific connections have specific functions. As we grow, connections become more specialised for their particular tasks, and talk less to other functional areas. Under the influence of psychedelics, this segregation can shatter, and previously unconnected areas of the brain can start to interact. The enhanced connectivity of the visual and auditory parts of the brain may explain the hallucinations that are experienced shortly after taking a psychedelic.

Safety first

Psychedelics do not lead to addiction, and so far, no death by overdose has ever been registered. However, the outcome of the psychedelic experience (the ‘trip’) depends on the combination of two major factors: the set and the setting. The patient’s psychological condition is referred to as ‘the set’, while the environment in which the patient takes the psychedelic is ‘the setting’.

If the set and setting are not carefully considered, the psychedelic experience may result in psychosis: the ‘bad trip’. These can be terrifying experiences which often happen in recreational, unsupervised scenarios such as parties or festivals. However, if psychedelics are used in the presence of a psychotherapist in a controlled environment, the effects can be therapeutic.

Clinical evidence

Psychedelics have had a very troubled history. After the ban by the UN convention in 1971, research on psychedelics became illegal and scientific interest shifted towards other compounds such as ketamine and MDMA. This gap in the history of psychedelic research can be clearly seen in figure 3 and extended until 2006, when Roland Griffiths demonstrated the safety of psilocybin on healthy volunteers, followed by Charles Grob in 2010 with LSD. Once there was evidence concerning the safety of psychedelics, research started to blossom in a period known as the ‘psychedelic renaissance’. A meta-analysis of six randomised clinical trials on more than 500 patients showed how LSD could be extremely powerful in reducing alcohol dependence and was effective even after one single dose. In a pilot study in 2014, 12 out of 15 patients stopped smoking after psylocibin treatment. Psychedelics have potential to treat more than just addiction though, and a study in 2016 demonstrated how psylocibin and psychological support improved depressive symptoms in treatment-resistant patients.

These results, albeit encouraging, must be interpreted carefully due to the small size of the studies. Larger clinical trials are still needed to follow up on these findings. For this reason, in 2019, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) scheduled psilocybin as a ‘breakthrough’ therapy for treatment-resistant depression. This was the first big step by a public organisation to promote psychedelic research, after the ban in 1971.

Figure 3. A timeline of psychedelics research. After the convention on psychotropic substances in 1971, it became illegal to study these compounds. Only in recent years are we witnessing an increased interest in the field.

Future perspectives

Although psychedelic research is still in its infancy, one thing is clear: the stigma around these drugs is unjustified, and many exciting avenues are opening up in the field. One example is with microdosing, which is the repeated use of small dosages for a sustained period. Lower doses of psychedelics would not cause hallucinations but could still play a role in improving cognitive and affective processes. Preliminary reports highlight how even low doses of psychedelics can change connectivity in the brain, correlating positively with improved mood. In the near future, microdosing combined with psychotherapy could be employed to treat anxiety, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), or simply improve creative thinking and subjective wellbeing. Maybe one day it will be completely acceptable to add a couple drops of psylocibin to our coffees in the morning.

The psychedelic renaissance is happening, and it is happening now. The scientific community is slowly starting to realise the potential of psychedelics, now it is up to the public to reconsider their prejudices about these mind-opening drugs.

*This year’s judging panel was made up of: Craig Daly (Pharmacology Matters editor), Hannah Roughley (Pharmacology Matters editor), James Boncan (Pharmacology Matters editor), Josh Dignam (Pharmacology Matters editor), Lauren Taylor (Pharmacology Matters editor), Sorrel Bunting (then Engagement Manager at the Society), Taichi Ochi (Pharmacology Matters editor), and Sarah Bailey (Vice President Engagement at the Society).

Comments

If you are a British Pharmacological Society member, please

sign in to post comments.