Nanthana Gunathilagan is the runner up for the 2024 ECP Writing Prize. Judges felt her detailed article on bioprospecting put a spotlight on an important topic.

Introduction

Imagine you are on a journey in which every plant, animal and creature you see could potentially be developed into life-saving drugs. This is bioprospecting, but beneath the surface lies a web of complex ethical concerns such as the rights of indigenous communities and environmental preservation, entwined with improving global health. You find a plant with medicinal potential. Do you take the plant to strengthen global health, or do you respect the land and knowledge of the indigenous community and preserve the biodiversity?

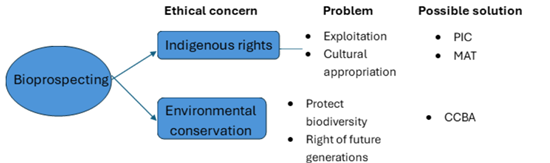

For decades, bioprospectors have been driven to develop innovative therapeutics with the power to save lives. While the origins of bioprospecting are uncertain, historical figures like Alexander Fleming, who discovered penicillin from mold, can be considered early bioprospectors, making significant strides in medical discovery. This article aims to shed light on the ethical concerns of bioprospecting (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The problems and possible solutions of bioprospecting

Ethical concerns

Indigenous Rights and Consent

Indigenous communities have rich cultural traditions and ancestral wisdom that have been passed down through many generations. However, all too often their ancestral knowledge is exploited without recognition or consent. For instance, colonial botanists recorded that the San people of South Africa were using plants of the hoodia genus as appetite suppressants, and in the late 20th century the South African Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) signed a licensing agreement with Pfizer. This led to hoodia products being commercialised for the Western weight loss industry. However, the CSIR did this without the San knowing. Thus, many argue that the San should have been informed about the use of their traditional knowledge and should have also benefited from the hoodia products.

Acknowledging and respecting indigenous people’s rights to their traditional knowledge and resources are essential regarding the ethics of bioprospecting. This is because successful bioprospecting frequently uses indigenous knowledge. For example, one potentially marketable drug is produced for every 10,000 chemicals obtained from the mass screening of animals, plants and microbes. However, the company Shaman Pharmaceuticals has a success rate of 50% due to advice from indigenous healers.

The most significant biodiversity is found in areas where indigenous people have historically lived. Indigenous communities also deeply value their ancestral lands due to their connections with the land. Thus, the lands must not be harmed by bioprospecting. Traditional ecological knowledge is important to indigenous communities because they have inherited rights to the knowledge, land and the biological resources. Thus, bioprospecting leads to the dilemma of the economy exploiting indigenous populations.

Frameworks preventing exploitation

In our pursuit of ethical bioprospecting, Prior Informed Consent (PIC) and Mutually Agreed Terms (MAT) principles serve as beacons of hope. They offer a pathway to justice, assuring that indigenous voices are heard and respected in the journey of pharmaceutical discovery. PIC is permission granted to a research institution by indigenous communities to utilise Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) and biodiversity. PIC thus ensures the protection of indigenous communities’ right to TEK and biological resources. It also ensures that bioprospecting will not occur if it will negatively impact the area. Moreover, PIC ensures fair benefit sharing of the use of biological resources and commercialised products. MAT also ensure the fair sharing of the benefits from the usage of traditional knowledge.

A possible pathway to prevent the exploitation of indigenous communities is research partnerships that involve engaging the indigenous communities as equal partners in the research process. This can help ensure that indigenous communities’ priorities and values are honoured and respected by integrating them into scientific methods.

Problems with the PIC and MAT frameworks

However, PIC and MAT have their shortcomings. It can be argued that benefit sharing is unfair because of the imbalanced power dynamics between indigenous communities and pharmaceutical corporations, as indigenous communities are less well-resourced thus have less bargaining power. Furthermore, in areas in which the government has limited capacity, there is a chance of individuals violating the agreements and principles. Bioprospectors may also not acknowledge or respect the cultural significance of biodiversity and traditional knowledge, leading to cultural appropriation.

Overall, PIC and MAT promote fair bioprospecting practices, but more development must occur to ensure the protection of the environment and increase fairness.

Environmental conservation

Negative impacts on the conservation

Biodiversity hotspots are regions that provide habitats to many unique, endangered and diverse species. Therefore, biodiversity hotspots might contain a great number of species with medicinal properties. As stewards of our planet, we must protect biodiversity like that found in hotspots, for the future generation.

Environmental conservation is an ethical concern during bioprospecting because bioprospecting can be detrimental to ecosystems if a keystone species is removed or over-harvesting leads to extinction.

A possible solution to this is using the Climate, Community and Biodiversity Approach (CCBA). This approach aims to combat climate change and conserve biodiversity hotspots. They create protected areas, habitat restoration programmes and encourage ethical bioprospecting. They carry out ongoing monitoring and evaluation to readily develop their conservation efforts. They also integrate indigenous knowledge into their decision-making and honour indigenous cultural heritage.

Positive impacts on the conservation

Despite these challenges, bioprospecting can benefit the environment. Providing funding to document biological resources creates a useful database for future research. Moreover, bioprospecting has sparked the discovery of new species, taxonomy research and biodiverse hotspots. Another environmental benefit is that biological feedstocks are used for industrial production instead of petrochemicals. This reduces greenhouse gas emissions and thus adds to efforts in combating climate change. Therefore, bioprospecting can positively impact the ecosystem.

Conclusion

As I ventured into the world of bioprospecting, the importance of valuing indigenous people’s rights and preserving our planet’s precious environment became increasingly clear to me. I urge each of us to reflect on our role in actively honouring indigenous rights and promoting environmental conservation. Our goal for bioprospecting should be to establish a balance between new discoveries and the principles of conservation and equity. Together we can pave the way for ethical bioprospecting which both upholds equity and the importance of preserving the richness of Earth’s biodiversity while improving global health.

Table of Definitions

| Abbreviation |

Full name |

Meaning |

| Bioprospecting |

Bioprospecting |

Searching for useful products derived from biological resources (eg. Plants and animals) that can be developed and commercialised to benefit society. |

| TEK |

Traditional Ecological Knowledge |

The knowledge that indigenous communities have about their local environment. |

| PIC |

Prior Informed Consent |

Permission granted by indigenous communities to utilise biodiversity and TEK. |

| MAT |

Mutually Agreed Terms |

A negotiated agreement between the bioprospectors and local indigenous community regarding the access to and utilisation of biological resources and TEK. |

Comments

If you are a British Pharmacological Society member, please

sign in to post comments.