A hobby is a poor word to describe a passion that has accompanied science all my life, and morphed from athletics to bike- and car-racing, with 60 years of competition, and 116,000 kms run (to date – I am not finished yet!). Like all good passions, it is rooted in some deep frustrations early in life. I have double vision when tired, and so ball games were sad in a school where rugby and cricket defined social status. I did make the school rugby fourth team – in a flu epidemic. Nevertheless, I was a pretty good runner, and loved it. However, hope for fame was dashed when my 14-year-old younger brother, Charles, ran away from the entire school, and me, in the cross-country – the first sign of a prodigious talent that would propel him to an Olympic medal and the English marathon record. Next, in my first senior 3-mile race I tried (with disastrous results) to beat a runner, who I later found out to be Lachie Stewart, in his final preparation for winning the Commonwealth 10,000m. This was to be an indication of my career, running behind first-class athletes! Humbling, but it improves you. The next revelation was running 10 miles in 53 minutes, so if I didn’t have my brother’s turbo, I had a good diesel engine.

Running fits into a scientific career, as you can just do it whenever you have time, and improvement is quite simple: the more you do well, the better you are. I find the simplicity of performance that is based on a stopwatch and seconds quite remarkable in a complex world. Sitting in stressful meetings is easy with your heart ticking away at 40bpm.

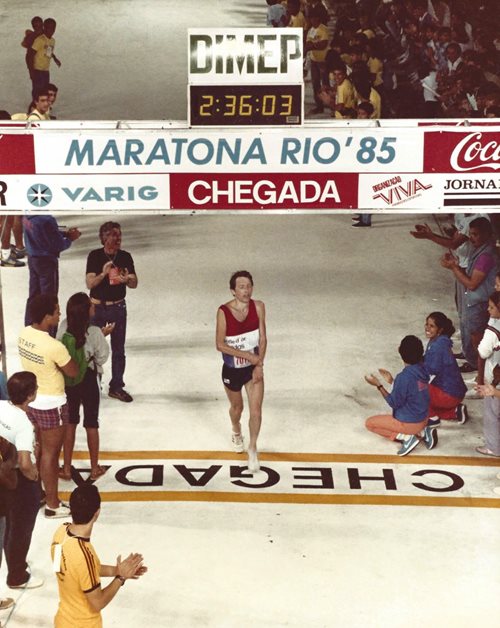

I moved to Alsace, to a top research centre, and joined the best distance running club in the east of France: it was a marvellous time, working, training (11 sessions a week) and racing flat out. My technician and I timed the experiments, so I could blast 5000m at lunch. The races were often held with wine fairs, a serious advantage. In one race, the club won the French–German 24-hour 1500m relay, where I ran 33x1500m relays flat out with 40-min recovery. I also became a good marathon runner, running regularly under 2 hours 40 min (but again nowhere near as good as my brother). Adidas France selected (and paid) me to run the South American marathon championships in Rio, in a French vest (I didn’t tell them I was British), where I had a brilliant race finishing on Copacabana, 33rd/10,000, running through an immense crowd, which just opened up in front of you, like the Tour of France. I was just outsprinted by the best runner in the south of France. An amazing experience.

Finishing 33/9000 in the South American Marathon Championships, 1985, for Adidas France, Rio de Janeiro

I moved back to Edinburgh, to take on the Syntex Pharmacology department and Edinburgh Athletics, another great club, but it was quite a cultural shock to swap Alsace wine villages for horizontal sleet in a Scottish housing estate. However, I got a reputation for turning up straight from work just before a race, warming up, and setting off! 8 years later I returned to France to set up Servier’s CNS research centre, and I thought of taking a semi-retirement in a little French club, only to find the two best runners could run 61-min half-marathons, and our veteran’s cross-country team won the county championship 8 years running. It was difficult fitting in running and setting up a research centre – I was once stopped by the police running home at 1am.

My performance was going down with age, so I tried bike racing for a few years, but I wasn’t as good. My wife made the mistake of giving me a voucher for driving a race car on a track and I was hooked by the power and concentration required. I bought a relatively cheap second-hand VX220 turbo, made by Lotus (photo), and found a garage run by a mechanic who had worked for the iconic race drivers Sebastien Loeb and Ayrton Senna. The car is set up beautifully, with 300HP for 900kg, and my data capture has seen 1.3g to the right and 1.3g to the left in <1s. I only do track-days, as racing is too expensive, but I finish shattered – sliding the car is an essential as maximum grip is obtained when the tires slide at 7°, so entering any corner, to get through quickly, requires charge transfer from 1.3g braking to 1.3g sideways at the corner apex, at 7°, wet or dry. Going through Eau Rouge at Spa Francorchamps F1 in pouring rain is an immense cerebral challenge, and my brain has speeded up to cope… I am still getting faster at 70, which is not the case running, although I continue with it too.

Dijon-Prennois race circuit, ~200kph

Does all this sport help my science? YES! When you’re fit, you have an incredible work capacity, and you can train your brain like your body. Sports science is underestimated in medicine. I had a little paper in Nature in 2012 on human evolution to run, how pharma has ignored this, because it is critical for age-related diseases, Alzheimer’s, schizophrenia and depression. This approach has given me a new lead (and a phase II drug) for motor neurone disease. Additionally, our research with the French sports science group has shown that human performance decline (which I am intimately associated with!) is the most precise measure of ageing, linked to mitochondrial function, which has powerful implications for ageing research. Furthermore, the physics of making a car go fast have revealed synergies with battery power that may have many uses.

And just as importantly, I still have great friends from all the running clubs I have been in.

Note: this article was written prior to regulations relating to COVID-19.

© Michael Spedding 2020

Comments

If you are a British Pharmacological Society member, please

sign in to post comments.